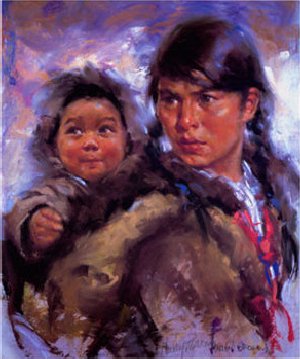

| Inuit Midwives

The Health eZine - Child Birth

The Evolution of Inuit Womenís Birthing Practices in Northern CanadaBy Heather Purdon - February 2008. With the creation of the new Nunavut Territory, most Canadians have been aware of the Canadian Arctic, but still many are not familiar about the Inuit that live there. I have been lucky enough to have spent six weeks on Baffin Island, in a small Inuit community called Pangnirtung in the Summer of 2000. The trip was in partnership with Trent University and the local Inuit community council. They were generous enough to provide to us an Inuit education, complete with Inuktitut language classes, to around 20 Trent University students that summer. This was one of the best experiences of my life, and one that forever changed my view of Canada and what the Canadian government offers to its people. In order to fully understand the role of the government in the North, we must recognize the history of governmental practices in regards to providing health services to those living there. Traditionally, Inuit women had their babies wherever they were on the land. As most traveled in family groups, when labor would begin there would be elders, sisters, mothers, and aunts helping with the delivery. Throughout the 1950ís, there was a legislative push for a sedentary Inuit existence. Churches, schools and health centers were created in Northern areas to entice the nomadic Inuit to settle in these areas which would in turn allow the Canadian government to gain greater control over the Northern population. Today, we can see the communities that sprung up during this time are still occupied today. Most Inuit still live in a traditional manner, hunting, fishing, traveling with the herds, and living on the land in summer camps, and is still the way of life. With the governmentís authority over health care, the Inuit had to change their traditional birthing practices to one that reflected westernized medicine. During my time in Pangnirtung, I was able to see the disjointed government theories that put Inuit women in an isolated and sterile environment to give birth to their children.

During the time I was visiting this Inuit community, women who were pregnant were flown to the nearest hospital in Iqaluit two weeks before their due date; this is often called the evacuation of women and is a perfect example of the governments hand in cultural disruption. In other westernized practices, or even in other areas of Canada, we are all under the strong impression that no woman should fly in their third trimester due to increased risk of inducing labor. But in this instance, the government has imposed a biomedical system that knowingly chooses to put thousands of women at risk. The change from the traditional way of birthing to this westernized system is one that the Arctic is trying hard to reverse. During the time I was there, if I asked pregnant women about using traditional Inuit midwives, or birthing in their own community, I was told this was not an option. The fissure of traditional practice and westernized medicine is more than just the flight to a hospital. Women are allowed to bring only one other person with them for the trip to the nearest hospital. As you can imagine, if the government is footing the bill for this flight and hospital stay, they would ideally like to keep it as economical as possible. This practice not only disjoints the family during a very special time, but puts pressure on the mother to choose the one person they would like to be at the birth. Traditionally a birth is celebrated by the whole family and community. Being flown out two weeks before the birth and days after the birth allows for a long and isolating experience for those who have no family relations in the community that houses the hospital. Having only one other person means you have only one support network during this time, and this goes against everything that is culturally sound with the Inuit. The fact that the Inuit continue to survive and thrive in the North is testament to the culture working together, the families being bonded together. In essence, child birth was a collective responsibility among the Inuit.

The elder Inuit population holds the skills of traditional midwifery within an Inuit framework and we need to keep that knowledge within the community. For so many years, these skills were bypassed in favor of contemporary western medicine. And now finally, the skills of the Inuit midwives and the knowledge of traditional birthing practices are returning to the North. Emphasis on recording traditional Inuit elders experiences with birthing have already begun to preserve the knowledge that the Inuit women held (Pauktuutit). To say this governmental practice was culturally disruptive would be an understatement. Yet, upon researching the changes that have happened over the last eight years, Iím happy to report some progressive transformations in these birthing practices. The women of the North are now speaking out about alternatives to the government standard on birthing in the North. A traditional midwifery program has been brought to Nunavut Arctic College, and these first steps have begun to weaken the strong-hold the government has on womenís birthing practices. There seems to be a shift in control back to the women who this affects and they are in turn, taking this control and creating healthier, more appropriate experiences for women.

There is a need for midwives in these smaller communities and Inuit women are beginning to change their birthing practices to reflect a more autonomous approach. At the very least, I hope this emphasizes the importance for all Canadians to understand some of the changes that are happening in the North. Also, giving the reader an understanding that standard government health care varies significantly in Canada depending on region. Further information on returning traditional midwifery to the Canadian Arctic can be found at the following websites: canadianmidwives.org/nunavut.htm

|

|